Why Eastern Europe's separatist republics love Putin and the Soviet Union so much

Quasi-states in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine have becoming willing pawns in Putin's game to rebuild Russia's sphere of influence

Today, May 9th, was Victory Day in Russia. For decades, this has meant dramatic military parades and homages to the USSR’s triumph over Nazi Germany in 1945, but this year, it has also meant glorifications of Russia’s ongoing quagmire in Ukraine. Vladimir Putin has connected Russia’s victory in the Great Patriotic War, as Russians call World War II, to his campaign in Ukraine through several ways, most notably framing the fight in Ukraine’s Donbas as a struggle to defend Russia itself, which, just like in 1945, is besieged on all sides once more.

Of course, another key part of Russia’s propaganda on Ukraine is the idea that it is fighting to protect Russian speakers there, which was a significant part of the justification for Putin’s recognition of the independence of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas several days before the start of the war. These quasi-states are less genuine separatist republics than Russian puppet states that have existed for years to fulfill a very specific purpose which Putin is now taking full advantage of to advance his rhetorical and military agenda in Ukraine.

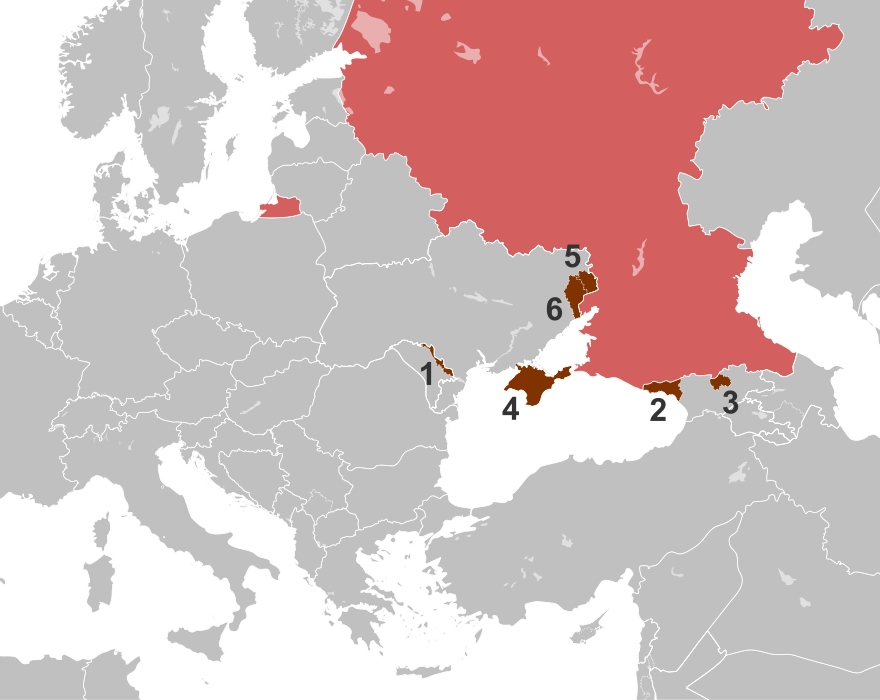

Donetsk and Luhansk are not the only places of their kind in Eastern Europe. In Georgia, the breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia have been dependent on Russia since the 1990s and de facto independent from Georgia since Russia’s invasion of the country in 2008, while in Moldova, the Transnistrian Republic along the country’s border with Ukraine has hosted Russian troops for years. Transnistria is back in the news in a big way — a few weeks ago, a Russian general explicitly stated that connecting Transnistria to Russian-controlled territory was one of Russia’s war aims in its southern Ukrainian offensive. Since then, several bombings have taken place in Transnistria, leading the territory to bar all fighting-age males from leaving its borders and its pro-Russian leaders to blame Ukraine for the violence, suggesting that Russia may be seeking to bring Transnistria into the Ukrainian conflict as well.

Why would tiny Transnistria be compelled to support Russia in its brutal war in Ukraine? The answer lies in the fact that Transnistria, like other post-Soviet breakaway republics, are hotbeds of Soviet nostalgia where a rose-tinted view of Soviet and Russian history has dominated national identity, yearning to create meaning in a post-Cold War capitalist world. These places have often utilized the aesthetics of the USSR in their symbology and political narratives, but in practice are motivated by several key ideas:

Putin’s nationalist project in Russia represents a return to the ideological sense of purpose that motivated the Soviet Union

Modern Russian nationalism is a counter-reaction to the vapid amorality of the post-1991 market economic system and the attempt to carve independent nation states out of the post-Soviet space

Russia and Russophilia are a path out of decades-long economic doldrums and crises of identity that accompanied the collapse of the USSR

Supporting Russia’s military maneuvers in the post-Soviet space is a way to guarantee a return to an imagined, long lost golden age

Out of both necessity and a nationalistic romanticization of history, political narratives in these breakaway republics treat the Soviet Union and Putin’s Russia as expressions of the same ideal. And in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Transnistria, Donetsk, and Luhansk are happy to be used as pawns in Putin’s project to turn back the clock and recreate Russia’s sphere of influence in the region, much like Abkhazia and South Ossetia were during Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008. For them, Russia is a liberator from aberrant post-Soviet creations like Ukraine and Moldova, and a rectifier of historic mistakes like Georgia’s absorption of Abkhazia and South Ossetia into its own territory.

1991 and the end of meaning

In mid-April, a Russian on-air host on the state TV channel Rossiya-1 made an interesting and strangely honest admission while watching a clip that purported to show Russian soldiers raising a Soviet flag above a police station in Mariupol: “An ideological war is taking place,” he said, “and you need to understand the psychology. It’s hard for citizens of a sovereign nation to accept that others are coming with the flag of another nation, even a formerly brotherly one, and their lands are going to them. But this flag of the Soviet Union, it’s a flag that unites.”

Such appeals to Soviet history will no longer work in Ukraine, but they have certainly worked for decades in the region’s breakaway republics. In fact, the clip being shown was not filmed in Mariupol at all, but rather 200 kilometers north in the town of Debaltseve in 2015. The soldier hoisting the flag isn’t a Russian, at least not on paper, and is instead a Russian-backed separatist of the Donetsk People’s Republic.

“Over the past 23 years Ukraine created a negative image of the Soviet Union,” Boris Litvinov, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the DPR, told The New York Times in an interview in 2014. “The Soviet Union was not about famine and repression. The Soviet Union was mines, factories, victory in the Great Patriotic War and in space. It was science and education and confidence in the future.”

Litvinov’s comment cuts to the heart of what motivates Soviet nostalgia in breakaway republics like the DPR — selective memories of the glories of the USSR, without any mention of the negatives that perpetuated its eventual breakup. And while a return to the USSR itself is impossible today, Putin’s incorporation of Soviet historical themes into his vision of Russian nationalism means that modern Russia has become a substitute for this nostalgia, a pathway toward reclaiming the greatness and meaning that life in the USSR once held for Soviet sympathizers. This is demonstrated by the steady rise in approval for Joseph Stalin in Russia in recent years, which has taken place concurrently with Putin’s consolidation of power and the rise in nationalism he has spearheaded.

Although the fall of the Soviet Union introduced millions of people to the prospect of national self-determination, democracy, and unfettered access to the global economy for the first time since World War II or even World War I, it also imposed upon them the vagaries and inequities of modern capitalism. With the exceptions of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, the post-collapse economic downturn of the 1990s left permanent marks on every single former Soviet state in one form or another. Although improvements in human development did indeed take place in the post-Soviet world, progress arrived unevenly, leading many communities to bear the burden of drastic wealth inequality, unemployment, and lack of opportunity.

In conjunction with these economic woes, for many people the end of the Soviet Union also meant the end of a powerful, ideologically-driven identity, which was replaced instead by local national affiliations that were more narrowly defined. What appeal does Moldovan identity have to someone who only ever saw themselves as a citizen of the Soviet Union? In many communities, such changes snowballed into an existential crisis of meaning, leading to a post-Soviet existence that simply did not live up to the hype. Such feelings were not always identifiable early on — in several modern post-Soviet breakaway republics, local leaders resisted the breakup of the USSR while it was happening and didn’t even have a chance to experience the post-communist world. Ethnic or linguistic conflict, rather than an attachment of Soviet ways of life, was often the immediate catalyst for these breakaway states to spring up. And yet in each of these partially recognized states, no matter the initial spark, Soviet nostalgia and a heavy attachment to Russia have come to define their political, economic, and social realities, largely because the conditions these quasi-states were aiming to preserve were intrinsically tied to the structure and history of the USSR.

From ethno-nationalism to Soviet nostalgism

Every single case of post-Soviet separatism arose out of various ethno-linguistic desires for autonomy, and yet with the sole exception of Nagorno-Karabakh (which I am not discussing here because its history is markedly different than the other breakaway republics), each of these quasi-states eventually adopted a neo-Soviet character with varying degrees of Russian nationalism emerging later on.

I’ll start with the DPR and LPR because they offer the most straightforward example of this trajectory. Both states came into existence in 2014 in the aftermath of the Maidan Revolution that toppled the pro-Russian government of Ukraine, and grew out of pro-Russian riots that broke out between locals and Ukrainian authorities. Soon enough though, they received unofficial backing from the Russian state, and Russian soldiers poured into the proclaimed republics to keep their separatist conflict alive.

Both the LPR and DPR have at various points adopted the styles of the USSR — the legislative body in both is called the Narodniy Soviet, meaning “national soviet,” officials in the DPR have stated that their aim is to create “military communism” in the republic, and at one point the Communist Party held a majority in the DPR’s legislature. Soviet symbols and flags have been heavily featured in both republics as well. Feeling little loyalty to post-1991 Ukraine as a nation-state separate from Russia, pro-Russian, Russophone communities in the country were able to tolerate the post-Soviet state of affairs only because they viewed Ukraine as an extension of Russia. Once that illusion was shattered in 2014, these separatists, with vital support from Putin, declared independence and quickly fashioned themselves as the renewers of the old Soviet order.

As I’ve explained previously, the memory of the USSR had a very specific appeal to certain post-Soviet societies as a foil to the newly independent states and economies that followed it. But it also offered a degree of ethnic agnosticism which is key to understanding the pro-Soviet and pro-Russian tilt of these breakaway republics. Prior to 1991, what language you spoke or which community you belonged to mattered rather little in a system where Soviet ideology, rather than nationalism, was the primary political motivator of the state, and where despite pretenses to the contrary, the Russian language ultimately reigned supreme.

In Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and elsewhere, ethnic and linguistic disagreements were largely put aside while these countries were all part of a single state ruled from Moscow, and only reared their head when the whole system collapsed.

That’s exactly what happened in Moldova as it lurched toward independence in 1991 and declared Romanian the sole official language, sparking tensions in Transnistria, a region where only a third of the population was ethnically Romanian. Long story short, Transnistria eventually declared independence from Moldova, touching off an intermittent, year-and-a-half-long conflict in the country that culminated in the breakaway region’s de facto independence in 1992. At the time, Transnistria’s population was roughly evenly split between ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, and Romanians, divisions that only came into focus after an independence, post-Soviet Moldova was created. For a wannabe state like Transnistria, the only way forward that made any sense was to align itself with its Soviet past, and in fact, Transnistrian leaders announced their intentions to apply to rejoin the USSR in 1990 before the Union itself came to an end. Now, decades later, Transnistria remains an anachronistic remnant of the Soviet Union, featuring frequent homages to Lenin, Communist imagery, and the hammer and sickle on its flag in the style of a constituent republic of the USSR.

Leaders in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, where separatist movements eventually led to armed conflict with newly independent Georgia, also tried to remain part of the USSR in 1990. Unlike in Transnistria, there were few sizeable Russian communities in these territories, yet their motivations for trying to cling to the corpse of the Soviet Union were largely the same — under the umbrella of the USSR, Abkhazians and Ossetians were able to enjoy a degree of autonomy and equality with other republics, and trying to remain a part of the Union seemed like the only viable alternative to likely second-class citizenship in a new Georgian state. Although the degree of Soviet nostalgism in the Georgian breakaway states is not nearly as over-the-top as it is in Transnistria today, Abkhazia especially continues to feature heavily Soviet-inspired cityscapes, and it and South Ossetia remain politically and economically dependent on Russia.

That’s because when the USSR fell, modern Russia was the only lifeline Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia had left. And with that lifeline came the inevitable shift from Soviet nostalgia in the 1990s and 2000s to an embrace of Putin’s vision of the Russkiy Mir — the “Russian World.”

The role of breakaway republics today in the “Russian World”

Soviet nostalgia didn’t spring up in every economically downtrodden post-Soviet community, and even where it did, it only rarely led to new republics declaring independence and surviving for years. The reason for this is simply because these states only arose in contexts where they were encouraged to do so by post-Soviet Russia for its own political convenience. And as Putin’s nationalist narrative for modern Russia continued to develop, he has taken advantage of the burgeoning Russophilia that grew out of Soviet nostalgia in these republics to advance his geopolitical strategy across the Russian near-abroad.

Putin’s deployment of a new Russian nationalist narrative based on patriotism, loyalty to the Kremlin, glorification of a revisionist view of Russian history, an us-against-the-world vision of Moscow’s place on the world stage, and a desire to “Make Russia Great Again” has given these breakaway republics a chance to blend their Soviet nostalgia with a new, forward-looking ideal. Now, rather than merely yearning for a bygone era, they can be proud of their place in “the Russian World,” which in Putin’s words is a civilization all unto itself.

Each of the five breakaway republics in question serves a purpose for modern Russia, and that’s no coincidence — although the national sentiments behind their formation may have been genuine, they have been able to maintain their independence solely thanks to Russian support. In Transnistria, the 14th Guards Army of the ailing USSR provided vital assistance for the republic in its war with Moldova, leading it to victory in 1992. Around 1,500 Russian “peacekeeping” forces have helped to safeguard the fruits of this victory ever since.

Russia has also maintained a troop presence in the DPR and LPR since 2014, and has set up permanent bases in Abkhazia and South Ossetia since 2008. Putin sees Georgia, Ukraine, and to a lesser extent Moldova as strategic buffer zones between the “Russian World” and Russia’s rivals to the west and south, and bolstering the independence of the breakaway republics there serves to maintain Russian power and influence over these countries.

Despite the appeal that Putin’s Russia may have for these breakaway states, their inclusion in the “Russian World” without the consent of the states they were carved out of has permanently trapped them within Russia’s orbit. Because their independence is not recognized by the vast majority of the international community, these breakaway republics have become cut off from their neighbors and thus are almost entirely economically, politically, and militarily dependent on Russia. In Abkhazia for example, tens of thousands of Abkhazians have been forced to obtain Russian passports since Abkhazian passports are invalid in almost every country on earth. Encouraged by their Russophilia, and with few other options, the DPR, LPR, Abkhazia and South Ossetia have each steadily inched closer to outright annexation by Russia in recent years.

With each of these states firmly under his belt through both soft and hard power, Putin has pulled the strings in these breakaway republics to suit his own ends in 2008, in 2014, and now in 2022. Not only have they allowed him to complicate domestic politics in Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova, but the LPR and DPR have aided Russian forces on the battlefield in the Donbas as well. It appears possible Putin may try to get Transnistria involved in a similar way in southwestern Ukraine sometime soon.

Due to all these myriad factors, these states as they currently exist are inseparably tied to Russia, and Russia is inseparably tied to them. Unless Russia’s foreign policy changes dramatically and they are forced to fend for themselves, these breakaway republics will have no choice but to continue to live in the alternate reality where the USSR is deified, and Putin’s Russia is the answer to the meaninglessness of post-Soviet existence.