Why Putin cares so much about Poland’s history with Russia

Putin and his allies are twisting Poland’s role in history to mask Russia’s imperial desires as self-preservation

Amid talk of war in Ukraine over the past month, Russian perspectives on the country’s history have been getting more scrutiny in the West than at any point in recent memory. Putin’s July 2021 essay titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” has received renewed attention recently because it lays out, in great detail, why Putin believes that Ukrainians and Russians should not be considered separate peoples — basically an extension of Putin’s claim that Ukraine “is not a country,” as the Russian leader infamously told George W. Bush in 2008.

Although the piece focuses on Ukraine, it reveals a great deal about Putin’s views on Russia’s historical relationship with Poland as well. I was surprised to find that references to Poland, its people, or its culture crop up 33 times throughout the essay, more than any other country other than Russia or Ukraine itself, and paint Poland as a heavy-handed occupier of Russian lands that is partially to blame for Ukraine’s modern separation from Russia. Such “reinterpretations” of Poland’s history with Russia have gathered steam in the Kremlin over the past few years, and on several occasions in 2019 and 2020, Putin has gone so far as to blame Poland for the outbreak of World War II itself — a mind-boggling claim given the events of 1939.

Why has Putin repeatedly characterized Poland as this threatening boogeyman in recent years? The answer comes down to three core ideas he holds about the country:

Poland is a Western proxy state in the heart of Eastern Europe that has historically served as an obstacle to Russian ambitions, including during recent crises in the region

Poland has been a source of disharmony between Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian people, whom Putin sees as a single nation

Poland’s historic rivalry with Russia before the 1700s has contributed to Russia’s paradoxical position as a simultaneous victim and an imperial power in world history

These claims are based on varying levels of historical revisionism and misinformation, and are motivated chiefly by a nationalistic view of Russia’s history that Putin has been pushing over the last several years. These views of Poland are particularly salient for Putin now because they contribute to the narrative that Russia’s position on NATO and Ukraine is a defensive one.

Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how Putin conceives of Poland’s history and why these conceptions fit into his current narrative:

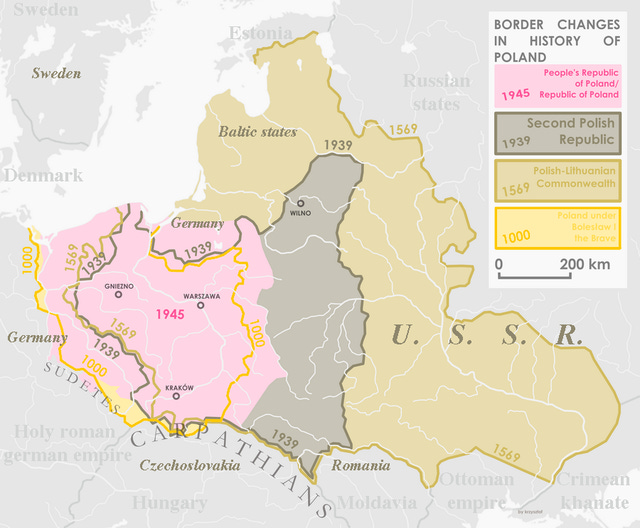

Poland vs. “A united Russia”

A seminal moment that has colored Russia’s attitude toward Poland since the early modern era was the Polish-Lithuanian conquest of Moscow in 1610. At the time, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a union state between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that was de facto dominated by Poland, was the largest polity in Europe. Russia meanwhile was on its knees — the Time of the Troubles was in full swing, and political and religious instability was rampant. Despite this, Cossack forces and a Muscovite volunteer army managed to defeat the Poles in 1612, ending Polish control over the Russian capital. The brief Polish occupation came to be seen as a proud moment in Polish national history given its later victimization at the hands of Russia and the Soviet Union, however at the time, it was a relatively minor episode in the Commonwealth’s wars with its rivals. In Russia on the other hand, the Polish ouster from Moscow took place at a major turning point in its history, marking the end of the Time of Troubles and the ascension of the mighty House of Romanov to the Russian throne a year later.

The event is celebrated in Russia on National Unity Day, a holiday which commemorates the apparent unity of all Russian people in opposing outside invasion, and a monument honoring the two generals who led the battle against Poland stands in Moscow’s Red Square today. Although the historical basis for the holiday was officially sidelined during the Soviet Union, it was notably reinstated by Putin himself in 2005. Against all odds, the events of 1612 continue to play a part in some Russians’ antipathy toward Poland today — during a soccer match between Russia and Poland in Warsaw during the UEFA Cup in 2012, Russian fans in the stands displayed a massive banner depicting Dmitry Pozharsky, one of the generals at the battle in 1612, that read “This is Russia” following street brawls between Polish and Russian fans. The game ended in a 1-1 draw.

The legacy of Kievan Rus’

The interpretation of the events in Moscow as a victory of a united Russian nation in the face of foreign occupation speaks to a deeper motivating factor for the Russian expansionism that has taken place ever since. Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine all claim national descent from Kievan Rus’, a loose, early medieval polity that united various East Slavic tribes and whose ruling dynasty would go on to create the Tsardom of Russia under Ivan the Terrible in the 1500s. The core of Kievan Rus’ withered and was conquered by the Mongols in the 1200s, opening the door for much of its westernmost lands to be seized by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania — which was itself united with Poland in 1569. In Putin’s version of history, the primary ambition for Russia’s subsequent expansion westward was not to impose its imperial hegemony on Eastern Europe, but rather to correct these errors of history and to win these lands back, just like the Russians won back Moscow from Poland in 1612.

Throughout his writings, Putin underscores the need for a reunification of the East Slavic-speaking peoples living in the lands of Rus’ by highlighting their alienation from Russia through centuries of divisive politics and forced Polonization under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although fluctuating levels of Polonization did indeed take place in Poland, Putin and other authors of modern Russian nationalism make a fundamental mistake we see time and time again in oversimplified historical revisionism: they view identity in early modern Europe through the lens of modern-day nationalism. National identity in Europe as we know it today is based on language, culture, and in some cases religion — if someone speaks Russian, practices Russian culture, and is Russian Orthodox, they are a member of the Russian nation. But before the 1800s, things were much more complicated, especially in multiethnic states like the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth where language was largely unrelated to one’s ethnic heritage or national affiliation. Given the multifaceted nature of identity at the time, it is unlikely that speakers of East Slavic languages living on the territory of Poland-Lithuania felt much of a connection with Russia in the modern sense of the phrase during the period as Putin alleges in his 2021 treatise.

Poland, the West, and foreign subjugation

As Poland grew weaker and the Russian Empire grew stronger, the tsars finally got what they wanted when Russia, Austria, and Prussia partitioned Poland between themselves, ending its sovereignty all together in 1795. Russia now controlled the entirety of the old Kievan Rus’ state — it had taken “what was ours,” as quipped the contemporary Russian historian Nikolay Karamzin, very much in line with Putin’s own thinking on the issue today. But in addition to taking the former lands of Rus’, Russia also seized significant parts of modern Poland and Lithuania as well — and even in subjugation, the Poles apparently found ways to menace Russian ambitions, according to Putin. In his treatise, Putin echoes conservative Russian thinkers of the time who claimed that independence-minded Poles, together with Austria, wanted “to exploit” the issue of Ukrainian self-determination for their own ends, in an apparent call-back to the image of the Polish nation as an impediment to Russian national unity and stability.

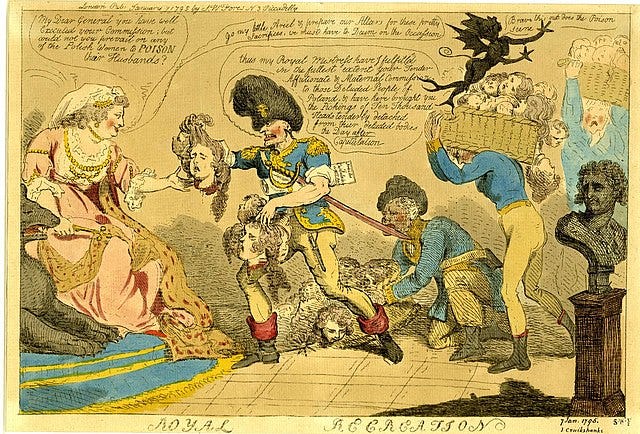

Poland’s long-running political and ideological connections to Western Europe have long contributed to this idea of Poles as a disloyal fifth column within the solidifying Russian imperial realm — Poland adopted a liberal constitution in 1791, allied itself with Napoleon as he waged war against Poland’s oppressors, and provided him with a springboard for his ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812. This historic association between Poland and the West has reemerged as a convenient focal point for Putin as he has moved to strengthen Russia’s position in Eastern Europe today.

The Borderlands and World War II revisionism

After ruling over both Poland and the non-Polish-majority Borderlands near-continuously for 123 years, Russia again lost them at the conclusion of the First World War in 1918 when Poland regained its independence. Soon afterward though, Poland’s attempts to reestablish advantageous frontiers in its east ran up against the Bolsheviks’ desire to spread the communist revolution to the rest of Europe, resulting in the Polish-Soviet War. The war culminated in the Battle of Warsaw in 1920 where, on the verge of defeat, Polish forces successfully repelled the Red Army and pushed eastward into modern-day Belarus and Ukraine. The subsequent Treaty of Riga secured a part of the old Borderlands for Poland once again, thus foiling Russian plans not only to spread communism into Western Europe but also to “unify” the lands of the ancestral Russian people once more.

Putin lamented the Treat of Riga in his writings and viewed the Soviet Union’s second invasion of Poland at the start of World War II as a corrective against its injustice. In what might be the understatement of the century, Putin wrote in his July 2021 essay that “[i]n 1939, the USSR regained the lands earlier seized by Poland.” In a June 2020 piece, published by National Interest for some reason, Putin patronizingly cited Russian security concerns and a desire to safeguard ethnic minorities, including Jews, from the Nazis as reasons for the Soviet invasion, and even suggested that the USSR did Poland a favor by occupying it:

“It was only when it became absolutely clear that Great Britain and France were not going to help their ally and the Wehrmacht could swiftly occupy entire Poland… that the Soviet Union decided to send in, on the morning of 17 September, Red Army units into the so-called Eastern Borderlines,” Putin wrote. “Obviously, there was no alternative.”

What actually happened was that the USSR seized much more than the just the Borderlands as Putin claimed, and conquered plenty of Polish-majority areas. It was by no means a benign occupation as Putin suggested either — Soviet occupiers instigated a reign of terror against their Polish subjects, murdered 22,000 Polish military officers in the infamous Katyń massacre, forcibly deported over a million Poles to Siberia, killed 150,000 Polish nationals, and arrested 500,000 Poles as political prisoners over the course of less than two years.

Putin engages in this gross historical revisionism in order to once again paint Russia as a victim of Western narratives about its history that, in his eyes, unjustly center Poland. The central argument of his National Interest piece is that Russia’s role in WWII has been judged unfairly, and that in fact the West — including Poland itself — deserved blame for the war. He tries to support this bewildering claim by alleging that Poland stood in the way of a security alliance between France and the UK on one side and the USSR on the other, which apparently left the Soviets with no choice but to sign the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Hitler. He maligns Poland even further by suggesting that it cooperated with Hitler during his invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, citing Poland’s seizure of Trans-Olza Silesia — a Polish-inhabited sliver of land less than half the size of Rhode Island — during the Sudetenland crisis. According to modern historians though, the idea that Polish authorities ever coordinated with Germans forces is baseless.

Of course, any forced annexation of territory in the modern period, no matter how small, deserves condemnation. But Putin’s aim in bringing up this historical footnote is not to argue against forced seizures of land — after all, Poland’s actions in 1938 are a drop in the ocean compared to what Putin’s own regime has done in the last fifteen years. Rather, like other Russian propagandists before him, he uses it to portray Poland as a dangerous aggressor even on the eve of its own conquest in 1939, and by highlighting its alleged opposition to the USSR’s security agenda in Europe, Putin is creating a through-line between the lead up to World War II and Poland’s current posture as NATO’s crown jewel in Eastern Europe in 2022.

What this means for Poland and Russia today

This core idea — that Poland is and has always been a Western-backed threat to Russian designs in its backyard — is ultimately more important for Putin than any territorial disputes over the Borderlands ever were. Despite the long-term damage that he alleges Poland did to the unity of the three Russian peoples, the Borderlands were ultimately severed from Poland in 1945 and annexed by the Soviet Union, once and for all ending at least the territorial aspect of that dispute. But both geopolitically and domestically, Poland continued to be a thorn in Russia’s side long afterward — it was in Poland after all where a Soviet-backed communist government was successfully overthrown for the first time in 1989, and Poland is one of Putin’s most vocal opponents in Eastern Europe today.

As Poland has ascended to the European Union and NATO, started hosting thousands of US soldiers, and strengthened its own military over the last two decades, Putin’s nationalistic vision of Poland’s history has become more relevant than ever, both in Russian national discourse but also in its sphere of influence. After Poland’s backing of the Belarusian opposition in 2020 and the migration crisis engineered by Belarus along Poland’s border in 2021, Putin’s lackey Aleksander Lukashenko used the same Czechoslovak example that Putin cited to allege that Poland’s military buildup foreshadowed a NATO-backed assault on his country — “They need ‘the whole of Belarus!’ Not just the Eastern Borderlands,” Lukashenko comically proclaimed in late January of this year. The Belarusian leader has also played into the idea that Poland is a Western puppet in the region, claiming that it and Lithuania would be “nothing more than dreary outskirts of Europe” without the United States.

The blind spot that enables this entire narrative is Putin and his allies’ inability to reckon with power relations — despite its one-time historic parity with early modern Russia, Poland has been on the receiving end of Russia’s imperial ambitions for hundreds of years since, and the only way this can be justified is by equating Poland with the ambitions of the West. At a time when Russia feels more claustrophobic in its sphere of influence than ever, Poland’s role in history is being twisted to mask Russia’s imperial desires as matters of self-preservation, and to rehabilitate its reputation as a trustworthy partner in Europe’s security matters. Putin’s historical revisionism is far from unique however — the Russian leader’s reopening of historic grievances is an unfortunate symptom of our times in which rival states use historical narratives as a cudgel to advance their nationalistic aims. And for countries like Poland and Russia, history is everything.

This is great article. It is a pity that neither Poles or Russians now theirs, and their neighbors history, forgetting even toxic nationalistic education. More Poles and Russians should read this article, regardless of events of past and coming weeks adding to the National frenzies. Since the author is de-mythologizing it, I would add some missing points. The first and most important is that the fight was and is not about the nations themselves, but about the model of society, citizens and their human rights. Human rights were always low in Russia. First hordes of Mongols kept population exposed to constant attacks and abduction. Then Vikings (Russ-bearded hence name Russia) kept their subject as slaves (Kristian in Russia means- farmer- why?) Rulers of Russia had always low regard for their own citizens, but were able to exploit their fears. First religious fears against Islam (that is why Serbs are so staunch allies in their war criminal trespass). Then fear of the Western human freedoms (that is why Russian army was invited by Polish backward aristocracy to partition Poland- to defend it from Western/French ideas). Russia has been always a wild-west (East) for outdated aristocratic leaders. Russians teach their subjects about Boris Godunov and claim he was killed by Poles. They do not teach about tsars being oppressors.